A Signet Ring for our 21st Century Family

Above: We each wear our signet rings on different fingers. Photography by Fiona Bailey unless otherwise noted.

Last year right before No. 2 son’s twentieth birthday, he requested a signet ring. Up until then, I was under the impression that signet rings were the preserve of those who already had them to pass down — in other words, a symbol of some sort of club — one where we weren’t members. My two sons are mixed race or hapa . They are ½ Chinese, ¼ Japanese and ¼ Anglo American. Having grown up in the UK, they view themselves as British despite their American parents — my husband and I have raised them to respect and appreciate diversity. Bemused, my initial reaction was to ask, “Why? Your lineage is so not straightforward, it couldn’t possibly be summed up into one signet”

Cursory research did little to reassure me. “Signet rings have been around since people wore jewelry,” says Beatrice Behlen, senior curator of fashion and decorative arts at the Museum of London. They seem to always have been popular, but I believe they became more popular with the rise of the bourgeoisie. Members of the middle class would not have a coat of arms, so having a signet ring would be a prominent sign to show that you are of a higher class.” The reverse snob in me was wary.

Above: No. 2 Son tells me that his ring reminds him of family and home when he is away at university.

And then I remembered that when I was in my 20’s, I had also found the signet ring a concept of great intrigue. I started to reconsider No. 2 Son’s request when I realised he was merely probing his identity like I had. Growing up in New England during the 60’s and 70’s, we were the only Chinese family in our community and I was constantly trying to understand where we fit in. My father and grandfather frequently regaled us with heroic stories about our Chinese ancestors and their game changing inventions like gunpowder and pasta. And yet, they could tell me little about our own family beyond two generations — one more thing they had lost in their emigration, under duress, from China to America before the war. My mother had lost both of her parents when she was young — her father died in 1946 fighting the Communists in the Battle of Siping and her mother passed away from cancer a few years later. This meant there was very little she could remember even if she wanted to — which she didn’t. Proud if a little unsure of my uprooted and slightly inaccessible heritage, I devised a story line where I became a descendant of Marco Polo, granting me access to an immediately accessible Italian one. Overnight, I became the great great great great great… granddaughter of the man my friends believed to be the father of spaghetti — our favourite food at the time. Even at eleven, I realised that if a man travelled in a country for seventeen years, he might get a little lonely. In my father’s concern for the “born out of wedlock” implications this story might cast on my family, he was less than pleased about my creativity. I was envious of those who were so confident of their histories that they had rings to wear which spoke assuredly of family heritage.

According to Behlen: “Today, signet rings are not necessarily the prerogative of the aristocracy or men. Anyone can wear them, and if someone wants to make up their own crest, why not?” It didn’t take long for me to realise that a signet ring which weaves together all the strands of our families’ histories — one that fully represents my sons’ mixed heritage — was an exciting design opportunity. This signet ring would be about consolidating a twenty-first century family’s indentity.

Above: When I met my husband at graduate school thirty years ago, I told him I would consider marrying him just to see what our children would look like.

I presented my signet ring proposal to the other members of my family, which to my surprise was greeted with a rare consensus. The disagreement I would have expected at the outset manifested instead in a minor detail. — each family member had a different finger in mind for their ring. Even more surprising was that my highly opinionated family members were giving me carte blanche on the design. I began with trepidation. A search for my husband’s surname revealed that Hanway is originally Irish — deriving from the pre-10th century Gaelic “O’hAinbhith” — with the rather compelling meaning of “the male descendant of the stormy one.” “Evocative,” I thought. “I can work with that.” The predictably heraldic family crest, on the other hand, felt the opposite. Closed and remote from whom my family are now, the crest was not going to be included in the design.

Above: The “stormy” Hanways.

The brief was simple — a design that would always remind the boys of their unique background.

I started with an “H” for “Hanway” and then chose the Chinese character for my mother’s maiden name of “Han” because of the convenient way “Han” slots in with “Hanway”. The ethnic group from which we derive happen to be the Han Chinese, albeit a different character to my mother’s surname.

Incorporating my husband’s Japanese heritage from his mother was more of a challenge until I remembered that “Hanway” means “the male descendant of the stormy one.” According to Surname DB, “the vast majority of Gaelic surnames originate from a nickname for the original chief or leader of the clan. Some of these nicknames were very robust, the famous Kennedy name meaning ‘Ugly head’. Presumably the original chief of the O’Hanveys had either a stormy temperament or drove his opponents off like a storm!” Those who have dared to cross the male members of my family on a sports pitch would confirm that those tempest genes still run strong. And the most powerful image I could think of to match those strong genes is the famous woodblock print “The Great Wave of Kanagawa” by the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Hokusai.

Above: On his gap year, No. 1 Son went to visit Wuzhi Mountain Military Cemetery in Tapei, Taiwan, the burial place of his Great Grandfather Han, a general in Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army, who was killed in the Battle of Siping in 1946.

With brief in hand, I turned to London-based jeweller Sian Evans. Having interviewed her last year for Fabulous Fabsters in Slow Jewellery Stories, I was drawn to her acute understanding of human narrative and the relationship we have with jewellery as a form of expression. Instigated by her lifelong passions in geology and archaeology, she is also committed to making jewellery which causes minimal impact to the environment and works to the mantra of, “Do no harm. Rethink. Recycle. Redesign,” We had a few pieces of sentimental family jewels that had languished in a jewellery box for years — including my husband’s platinum wedding ring which he says “shrunk” in the wash. I was very attracted to the idea that Sian could transform these pieces into something we would want to wear. My final instruction to Sian before I left her to get on with the ring design? “I don’t know how you’re going to do it, but the wave must be included.”

Above: Sian’s initial design sketches.

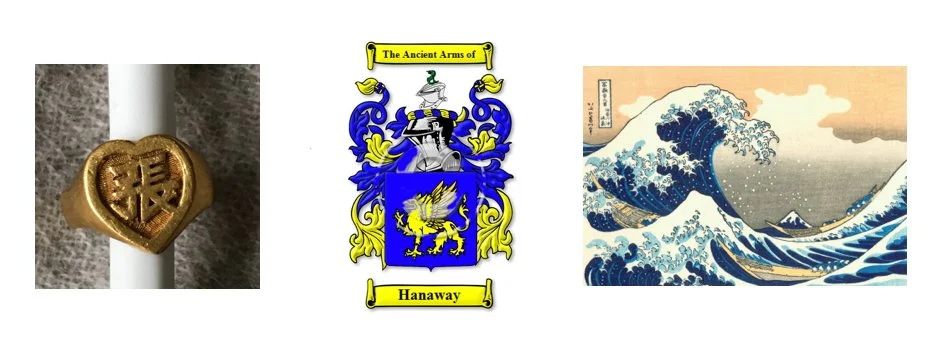

Above L: A solid gold ring with the kanji for Chang, my last name, that my parents had given me when I was 10. This was one of the pieces that was melted down to create the new rings. Above M: The Hanway crest. Above R: The “Great Wave of Kanagawa” by the Japanese artist Hokusai.

Above: The way the light hits the face of the signet ring determines whether the “H” or “Han” kanji is more visible.